A path less travelled

Hiking the newly-established Via Glaralpina trail around Switzerland’s Glarus Alps, and then meeting the volunteers who built it.

Tucked away on the northern flank of the Alps, Glarus is much quieter than neighbouring cantons in Switzerland. The steep topography and absence of any 4000-metre peaks seems to have deterred ski resort and road developers, as well as many tourists. But the dramatic terrain in the Glarus Alps (known locally as Glarnerland) is also an asset.

A growing population of wolves is a recent indicator that this region still offers a rare sanctuary from civilisation. But can a balance be struck between preserving Glarnerland’s quiet character, whilst encouraging more visitors?

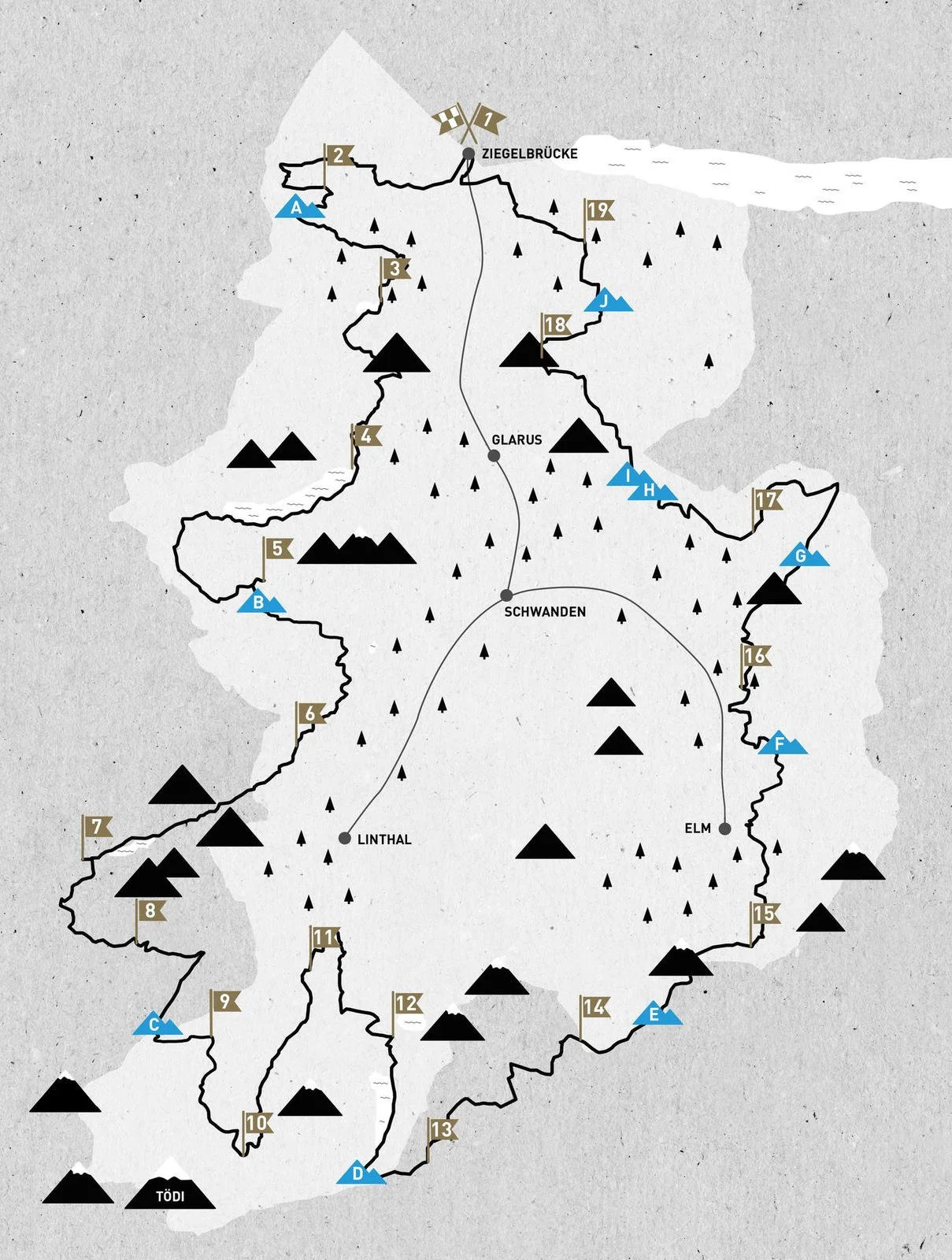

Perhaps this is what inspired a team of local volunteers to develop the Via Glaralpina: a long-distance hiking trail that traverses the Glarus Alps in a 230km loop. Completed in 2020, the trail is easily accessed from Zurich and divided into 19 stages. Each stage ends at an alpine hut or village.

“The Via Glaralpina is spectacular… I think it’s the alpine stages that make it so unique in Switzerland,” - Gabi Aschwanden, Via Glaralpina creator.

Alpine Trails

It was the challenge of moving through high mountains that inspired me to walk the Via Glaralpina. Roughly one third of the route leads through alpine terrain, where the route is way-marked but often without a defined footpath. Having already done a lot of walking in the Alps, I sensed the Via Glaralpina offered wilder terrain than most established long-distance trails.

The Plan

Eager to drink in the solitude and freedom of the mountains, I planned to wild camp every night of my hike rather than using accommodation. By carrying a lightweight bivvy setup, I also hoped to travel fast enough complete the 230km route in nine days.

The Via Glaralpina makes a total ascent of 18,500 metres, so I needed to climb about 2000 metres every day during my journey. I also planned to divert from the trail to climb the adjacent peaks of Gletscherhorn and Hausstock. It all started to feel slightly overambitious when I learned that the weather in September had been unusually stormy.

Luckily, the skies were settled when I arrived in the village of Matt, situated high in the Sernf Valley. The Via Glaralpina forms a loop around Glarus, which can be hiked in either direction and started from several locations. I’d chosen to begin my trip at the wonderful and welcoming AktivHostel Hängematt, before travelling clockwise. Beginning in the south allowed me to cover the highest terrain early on, whilst I was more certain about the weather forecast.

Above: overlooking the Sernf Valley.

Mind-bending geology

During the first two days, the trail led me high above the Sernf Valley and into the Sardona UNESCO World Heritage Site. It was a landscape of immense cliffs topped by serrated peaks.

The Glarus Alps were originally formed during an enormous thrust event. This involved tectonic plates colliding over millions of years to push huge swathes of rock upwards for thousands of metres. Older rocks were left resting on top of younger rocks and because of this, the mountains in Glarus are said to be upside down.

The cliffs above the trail appeared like giant slices of a layered cake. Huge horizontal bands of rock, called strata, stretched across them. I could often trace their course onto the surrounding peaks as well. The missing chunks of strata in between the mountains had been carved away during subsequent eras of erosion and glacial activity.

Above: the '“magic line” cutting across the cliffs of Hausstock.

Below: folded rock above the Linth Valley.

Shifting landscapes

The contrasting terrain just kept on coming. On day three of my walk, I briefly left the Via Glaralpina to climb the east ridge of Hausstock. The 3158m peak rose above a labyrinth of ridges and steep valleys to reveal the glaciated summits of Tödi, Clariden and Bifertenstock.

The following day, the trail led me directly beneath these peaks and then traversed the fringes of Clariden’s glacier. Despite there being a mountaineering feel about the landscape, the Via Glaralpina never strayed into any technical terrain.

Walking beneath the snaking tongue of the glacier, ancient worlds revealed themselves to me in the rocks beneath my feet. My perception of time crumbled as I stared at the fossils of 125 million year-old sea creatures etched into alpine moraine.

Above: crossing the fringes of Clariden’s glacier.

Below: Fossilised rudists or oysters, probably in so called “Schrattenkalk” from cretaceous time (125 million years ago).

Urner Boden and the Mären Plateau

From the icy landscape, I descended into the scenic pastures of the Urner Boden valley. Jangling cowbells serenaded me as I restocked my food supplies at a village shop.

The limestone cliffs above Urner Boden were packed with rock climbing routes, but the Via Glaralpina revealed a straightforward ascent amongst them to enter the Mären Pleateau.

The plateau is the largest karst limestone landscape in Switzerland. I followed painted way-marks through its maze of sinkholes, caves and tiered crag bands. Despite the mesmerising rock formations, I couldn’t help noticing a darkening sky to the west.

Above: descending towards Urner Boden beneath the Klaussen pass.

Below: the Mären Plateau is the largest karst limestone landscape in Switzerland

Bad weather

I only just managed to race over the Furggele Pass before a big storm hit. My decision to hike beyond the cosy hut at Glattalp felt foolish as my little tarp tent blew down twice during the night, soaking all of my kit.

A day of rain followed as the Via Glaralpina led me into the Glärnisch massif. I’d seen nobody all day until some very soggy llamas emerged out of the clag. They were the last animals I’d expected to find grazing on a Swiss mountainside.

Leaving my new friends behind, I arrived beneath the high pass of Zeinenfurgglen. Melted folds of rock and glaciated slabs had formed a narrow breach in the cliffs. Even without any footpath, the way-marks of the Via Glaralpina led me safely over them.

From there, I descended into forests to reach the fjord-like Klöntalersee. I decided to stay at a little campsite beside the lake so that I could dry out and recharge.

The following day, I was once again thankful for the painted way-marks, as I crossed high ridges inside of a wet cloud to traverse the peaks of Wiggis and Rautispitz. By night six, I was halfway through the route, but the wet weather was grinding me down.

Rescued by Bruno

In an attempt to seek shelter from the increasing high winds, I pitched my tent in the lee of a slope. My plan worked until the wind spun around. The tents’ walls crumpled beneath huge gusts and it started raining.

I packed down in the dark and hiked to the nearest farm, where I nervously knocked on the door. A stern-looking farmer appeared beside his suspicious dog. They stood silently as I babbled in broken German until the farmer cut me short and said, “come with me”.

He led me into a barn which was packed full of cows. I cowered in a corner as the farmer began herding most of them outside into the rain. My reluctant roommates mooed angrily in protest, and left a tidal wave of cow pat across the floor. I was allowed to sleep in the hay until the cows were milked at 6am.

I awoke in the morning after the best night’s sleep I’d had in ages. I thanked Bruno the farmer, who had luckily come to find the whole situation pretty funny by then.

Above: Bruno the farmer outside of his barn, where I slept!

The home straight

Having crossed a serrated, limestone ridge called the Brüggler on day seven, I reached the northern boundary of Glarus. Mellower terrain and calmer weather had finally arrived.

To complete the Via Glaralpina, I just needed to cross the mouth of the Linth Valley via the small town of Ziegelbrücke, before heading southwards across the mountains again for two more days.

I slowly dried out whilst ascending above the sunny shores of Walensee. Beneath me lay vineyards and picturesque villages. From there, pristine forests welcomed me as I scoured the footpaths for wolf tracks.

The presence of wolves in Glarus is a controversial issue, particularly amongst the local farmers who have lost livestock to them. To an outsider like me though, it felt exciting just to know that these apex predators were still surviving in the Alps.

I never saw any signs of them, but as the route traversed high ridges beside the Mürtschenstock massif, I watched golden eagles soaring above the cliffs. There were also herds of chamois idly grazing amongst the hanging valleys and glacial tarns below me.

I reached the peak of Gufelstock on night eight and found a five-star camp spot above the forested slopes of a remote side valley. I’d barely seen anyone all day.

The final day of my journey saw me re-enter the Sardona UNESCO site, before following a five kilometre-long ridge to a peak called Gulderstock. It provided a final opportunity to look out at the mountains which I’d traversed during the previous nine days.

The Via Glaralpina had unlocked a different way of seeing the mountains. I’d never fully appreciated the world of geology before, but the striking rock formations in Glarus had brought it to life. Uncluttered alpine landscapes and abundant wildlife had left me with a slightly firmer grasp on the staggering age and complexity of our beautiful planet.

“Enjoy nature with all your senses. When you hike on the Via Glaralpina, you will find much more than you were looking for,” were the words of Via Glaralpina creator, Gabi Ashwanden.

Above: lakes beneath Gufelstock.

Below: standing beneath Gulderstock at the end of my walk.

Meeting the creators

The Via Glaralpina was created by a close-knit team of local volunteers. After completing my walk, I chatted with Gabi Aschwanden and fellow trail-builder, Heidi Marti.

“Our canton is very small, but very innovative. If you are enthusiastic about an idea, you will find people who will support you,” Gabi explained.

Heidi and Gabi have spent their lives working in alpine huts and maintaining the footpaths around Glarnerland. In 2016, they began building the Via Glaralpina because they wanted more people to come and experience their home. They also hoped the trail would increase traffic for local businesses, but in a sustainable way.

“The nature here is all that we have for the tourists,” Heidi explained.

I learnt how Heidi and Gabi had scouted and way-marked the high alpine sections of the Via Glaralpina by themselves.

Their tireless work hand-painting all of the way-markers had also presented some unexpected challenges.

“One afternoon we became so sleepy, but also we couldn’t stop laughing,” Heidi said.

As they continued working, Gabi hallucinated, imagining a man with a bell. Eventually they realised that they’d been breathing in toxic fumes from the blue paint!

“They were long, long days. We would start at 6am and finish at 9pm,” Heidi explained. “When working on the high ridges, we also had to carry a lot of water,” she added.

“We Glarner people are courageous, and that is certainly to our advantage.” Gabi said.

It was inspiring to learn how a small group of volunteers had created such a captivating long-distance trail. Between them, they’d managed to thread an un-intrusive pathway through sensitive and complex landscapes.

Although the sprawling ski resorts of Flims-Laax lay just beyond the ridges of Sardona, the Glarus Alps still exist in their own, much quieter world. I sense that the people in Glarnerland hope to keep it that way.

Above: Heidi Marti painting way-marks on the Bruggler.

How to walk the Via Glaralpina

Getting there:

The Via Glaralpina is easily accessed from Zurich. A one-hour train ride leads directly to Ziegelbrücke, which is the most popular starting point of the trail. It’s also easy to hike individual sections of the route, as most of the valleys are well-served by buses. Train and bus times are easily found via the SBB Mobile app.

Accommodation & Resupply:

Each stage of the trail provides opportunities to stay in staffed, alpine huts or guesthouses. The only exception is above Panixer Pass, where the hut is unstaffed. Wild camping is also permitted in some areas of Glarus, but make sure you check current regulations via sites like the SAC. Laws state that you must camp above the tree-line and outside of any private property or protected nature reserves. Your tent can’t be pitched during the day and stoves are banned during periods of high forest fire risk. This information can be monitored using the Swiss Topo app. Food resupply is possible in several small villages, but Ziegelbrücke is the only town on the route. Beware of Swiss opening hours!

Maps and guidebooks:

For GPS navigation, I recommend using the Swiss Topo app. For paper maps, the Wanderkarte Glarnerland 1:50,000 covers the entire area of the Via Glaralpina. 1:25,000 scale maps are also available. Although written in German, the Via Glaralpina guidebook features overview maps and photographs of the route. The trails’ website also contains lots information: www.via-glaralpina.ch

Difficulty:

Although the Via Glaralpina ventures into remote, alpine terrain, the technical difficulty of the trail itself never exceeds UK grade 1 scrambling. Metal chains provide assistance on the most exposed, rocky sections. Despite the absence of a trail during the highest stages, the way-marking is always very thorough. Harder parts of the route can be bypassed by taking alternative paths. Beware if attempting the route in early summer or late autumn, as steep snowfields would make it a very serious proposition.